Organ-on-a-Chip Technology Shows That Probiotics May Not Always be Beneficial

An advancement in organ-on-chip technology has led to new information regarding popular gut health supplements and a better overall understanding of the human gut.

Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin used computer engineered organ-on-a-chip technology to discover the mechanisms of how diseases develop, specifically in the digestive system.

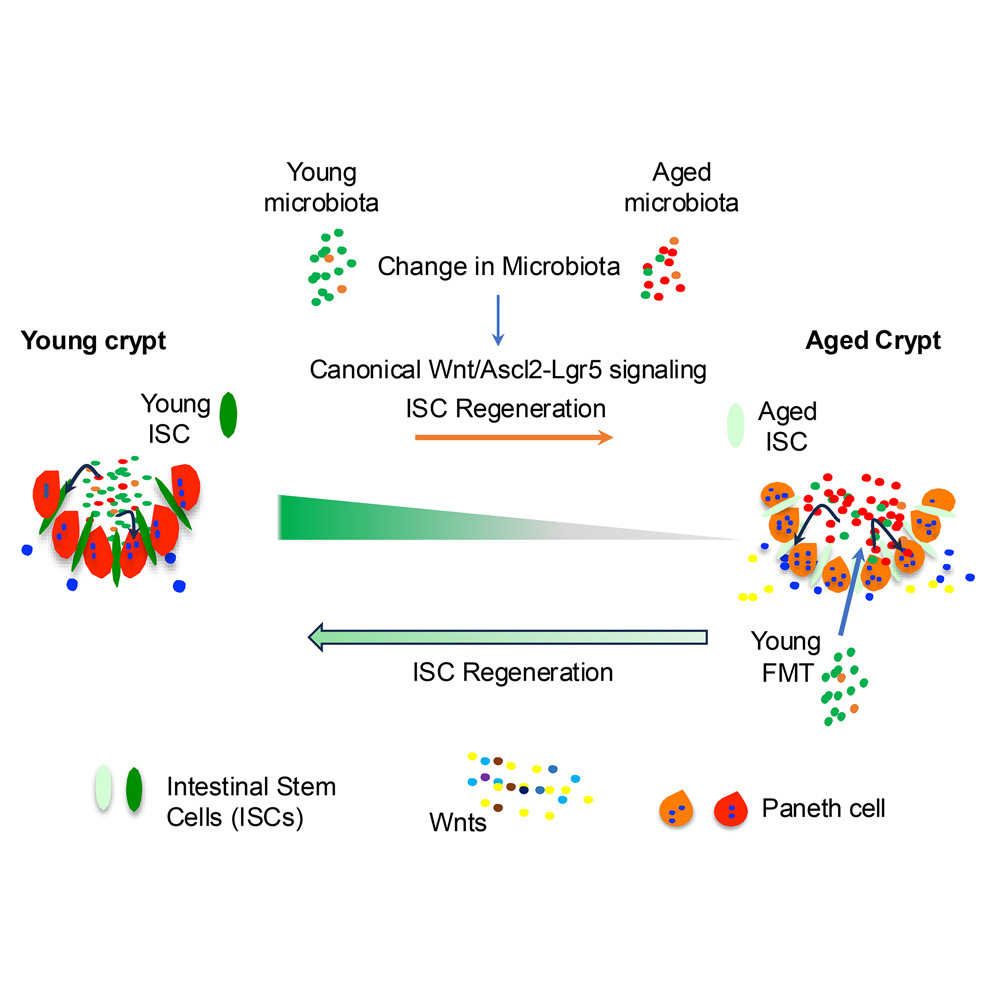

The new microphysiological gut information-on-a-chip system enabled the team to confirm that intestinal barrier disruption is the onset initiator of gut inflammation.

The researchers also discovered that probiotics—live bacteria found in supplements and food such as yogurt that is often considered good for gut—might not be beneficial to take on a regular basis.

“Once the gut barrier has been damaged, probiotics can be harmful just like any other bacteria that escapes into the human body through a damaged intestinal barrier,” Woojung Shin, a biomedical engineering PhD candidate who worked with Kim on the study, said in a statement. “When the gut barrier is healthy, probiotics are beneficial. When it is compromised, however, they can cause more harm than good. Essentially, ‘good fences make good neighbors’.”

According to the study, the benefits of probiotics depend on the vitality of the person’s intestinal epithelium, a delicate single-cell layer that protects the rest of the body from other potentially harmful bacteria found in the gut.

“By making it possible to customize specific conditions in the gut, we could establish the original catalyst, or onset initiator, for the disease,” Hyun Jung Kim, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, said in a statement. “If we can determine the root cause, we can more accurately determine the most appropriate treatment.”

The identification of the trigger of human intestinal inflammation can be used as a clinical strategy to develop effective and target-specific anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Previously, organs-on-chips—microchips lined by living human cells to model various organs from the heart and lungs to the kidneys and bone marrow—were an accurate model of organ functionality in a controlled environment. However, the new study represents the first time a diseased organ-on-a-chip has been developed and used to show how a disease develops in the human body.

The researcher’s next plan to develop more customized human intestinal disease models for other diseases like inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer. These other models will enable them to identify how the gut microbiome controls inflammation, how cancer metastasizes and the overall efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

News source: www.rdmag.com